What Do They Pay?

Towards a Public Database to Account for the Economic Activities and Tax Contributions of Multinational Corporations.

Executive Summary

This paper reviews the prospects for a global public database on the tax contributions and economic activities of multinational companies. It is divided into four main sections. Firstly, we present a set of user stories, questions, requirements, and scenarios of usage for a database. Secondly, we look at what kinds of information a public database could and should contain. Thirdly, we look at the opportunities and challenges of building a public database drawing on various existing information sources. Fourthly and finally, we suggest next steps for policy, advocacy, and technical work towards a public database.

Table of contents

Acknowledgements

This report would not have been possible without input from and discussion with the following individuals and organisations:

-

- Liliana Bounegru

- Researcher, University of Groningen + University of Ghent + Digital Methods Initiative

-

- Mareen Buschmann

- Policy Adviser, Save the Children UK

-

- Tim Davies

- Research Affiliate, Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society, Harvard University

-

- Dominic Eagleton

- Senior Campaigner, Global Witness

-

- Tommaso Faccio

- Lecturer, Nottingham University Business School

-

- Luke Gibson

- Tax and Inequality Policy Advisor, Oxfam GB

-

- Daniel Haberly

- Lecturer, University of Sussex

-

- Hera Hussain

- Community & Partnerships Manager, OpenCorporates

-

- Petr Janský

- Assistant Professor, Charles University in Prague

-

- Michael Jarvis

- Executive Director, Transparency & Accountability Initiative (T/AI)

-

- Emily Kenway

- Director, Fair Tax Mark

-

- Matti Kohonen

- Principal Adviser (Private Sector), Christian Aid

-

- Lucy Kimbell

- Founder, Data Studio + Director, Innovations Insights Hub University of the Arts London (UAL)

-

- Thomas Lassourd

- Senior Economic Analyst, Natural Resource Governance Institute

-

- Sam Leon

- Data Advisor, Global Witness

-

- Henri Makkonen

- EU Advocacy Advisor, Financial Transparency Coalition (FTC)

-

- Charlie Matthews

- Head of Advocacy, ActionAid

-

- Nick Mathiason

- Director, Finance Uncovered

-

- Jean Mballa Mballa

- Director, Centre Régional Africain pour le Développement Endogène et Communautaire (CRADEC)

-

- Sabine Niederer

- Founder, Citizen Data Lab + Researcher, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences

-

- Robert Palmer

- Director of Partnerships and Communication, Open Data Charter

-

- Oliver Pearce

- Policy Manager (Tax and Inequality), Oxfam GB

-

- Sol Picciotto

- Emeritus Professor, Law School, Lancaster University

-

- Stephen Abbott Pugh

- Portfolio Manager, Open Knowledge International

-

- Katelyn Rogers

- Project Manager, Open Knowledge International

-

- Indra Römgens

- Researcher, Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO)

-

- Anton Rühling

- Programme Manager, OpenOil

-

- Cécile Schilis-Gallego

- Data Journalist & Researcher, International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ)

-

- Prem Sikka

- Professor of Accounting, Essex Business School, University of Essex

-

- Zosia Sztykowski

- Project Manager, OpenOwnership

-

- Tommaso Venturini

- Research Fellow, Institut National de Recherche en Informatique et en Automatique (INRIA)

-

- Francis Weyzig

- Policy Advisor (Tax Justice and Economic Inequality), Oxfam Novib

-

- Lisa Wise

- Head of Inclusive Development, Save the Children UK

-

- Dariusz Wojcik

- Professor of Economic Geography, St Peter's College, University of Oxford

-

- Mark Zirnsak

- Tax Justice Network Australia

We also wish to extend our thanks to students and researchers at Charles University in Prague and King’s College London for their input in collecting and exploring CRD IV data. Finally we would like to thank all of our colleagues at the Open Data for Tax Justice initiative, which is coordinated by Open Knowledge International and the Tax Justice Network, and supported by a grant from Omidyar Network. If you or your organisation are interested in joining the network you can contact: contact@datafortaxjustice.net.

Introduction

Many of the policy proposals put forward by the Tax Justice Network (TJN) after its establishment in 2003 were so far from mainstream thinking about tax that it was difficult to find a policy audience with which to discuss them seriously (Murphy, Christensen & Kimmis, 2005). But by 2013, just ten years later, these proposals had come to form the basis for the global policy agenda - including "Country-by-Country Reporting" (CBCR) of the tax contributions and economic activities of multinational companies.

So common is the exposé of tax avoidance by multinationals today – think of headlines featuring Apple or Amazon, Google or Starbucks – that it would be easy to forget how recently things changed. But the Tax Justice Network’s first front-page media splash was only in 2007. Even the headline, ‘Revealed: How multinational companies avoid the taxman’, has become so familiar that it would be almost redundant today (Guardian, 2007).

Over the past decade, international media coverage and civil society campaigning has flourished. Investigative journalists have undertaken international collaborations highlighting the scale and societal effects of tax avoidance strategies. In many lower-income countries, the tax treatment of multinationals has risen to the top of policy agendas, driven by civil society mobilisation and public anger. In OECD countries, protesters have taken to the streets to oppose the minimal contributions of high street companies. The issue has caught the attention of populist political movements of various stripes.

By 2013, issues of tax were atop the global policy agenda too. The G8 and G20 groups of countries set the aim of reducing the ‘misalignment’ between the location of multinational companies’ economic activity, and the location of declared, taxable profits. The OECD was given a mandate to change international tax rules to achieve this end, including the specific remit to introduce a country-by-country reporting standard. While there are a range of benefits to this data being compiled and made public, the critical development is that it is intended to show for the first time exactly where companies do business, and the extent to which this is aligned – or misaligned – with where they declare profits. This is would not be a smoking gun to establish that a specific tax avoidance structure has been at play; but it could be a powerful instrument to help a variety of different actors to know where to investigate further, and what the scale of the problem may be.

The OECD standard for CBCR is technically very close to the original TJN proposal (Murphy, 2003) - but politically very far from it. The TJN proposal was for accounting data that it always intended be made public, to ensure the accountability to citizens of both multinationals and of tax authorities. The OECD data, in contrast, is to be provided privately to the tax authority in a multinational’s headquarters jurisdiction. It may then be exchanged, under a range of conditions, with other tax authorities in which subsidiaries of that multinational company trade. But under no circumstances are those tax authorities allowed to make the information more widely accessible. Longhorn et al (2016) provide a comprehensive analysis of various CBCR standards, their evolution and the arguments and evidence on their value.

Knobel and Cobham (2016) demonstrate the paths by which OECD reporting could exacerbate, rather than ameliorate, existing global inequalities in taxing rights with respect to multinationals. In addition to failing to respond to lower-income countries’ revenue losses, the lack of transparency means that the current standard will also fail to build confidence in the fair tax treatment of these high-profile taxpayers - missing an important opportunity to build tax morale and wider public support for tax compliance.

As things stand, if CBCR data is not made publicly available the OECD initiative would perhaps be the least transparent transparency measure imaginable. And yet, it marks an important step forward for CBCR. With most major multinationals now actually facing the obligation to comply with the OECD requirement, the argument about transparency has turned. The question now is no longer ‘Why should this information be collected?’ Instead, it is now ‘Why should this information, now collected, be kept secret?’.

The OECD is in some sense a late adopter, with multiple country-by-country reporting standards having been introduced since the original proposal. Notably, these include public CBCR for extractive sector companies in both the EU and US, and for financial institutions in the EU. There were also two notable attempts to include CBCR data in International Financial Reporting Standards, and although both failed the fact that this was not on technical grounds did prove that this data is within the scope of such standards. The data is, to be clear, accounting data rather than tax data: it reflects the location of activities, and is not an extract from a tax return.

That some variations on CBCR have been adopted does, however, mean that in the absence of any official attempts, there is the possibility for civil society to take steps towards establishing a public database of all available CBCR information. This could support greater use of the existing data by various stakeholders, from tax authorities to activists and journalists. The data produced may also be of some interest to investors, many of whom are now showing some awareness of the significance of this data. Importantly, it also provide a platform for the creation and testing of risk measures - above all, those that capture the extent of profit misalignment and therefore allow tracking of progress on the global policy aim of its curtailment. In addition, such a database would provide an avenue for companies that embrace transparency to begin unilaterally to publish their own CBCR.

Overall, the use of such data is likely to provide valuable evidence not only on the underlying issues of misalignment, but also on the challenges and opportunities of CBCR data. In particular, it may help to resolve questions on the need for data quality and consistency, and to motivate convergence towards best practice among existing and possible future standards. Over time, it is possible to imagine such a database being hosted within a more official setting such as the mooted intergovernmental tax body that could be created at the UN (Cobham and Klees, 2016).

For now, this report focuses on what a global public database could look like; what public sources of information already exist and which may be important to prioritise in addition; how far towards ideal CBCR it is possible to reach using existing sources; and what changes would be needed to strengthen the contribution from CBCR towards the shared, global policy aim of reducing corporate tax avoidance by curtailing profit misalignment.

Our aim is not to create the perfect, final product in terms of a public CBCR database. In their "Changing What Counts" report, Gray, Lämmerhirt and Bounegru (2016) emphasise the role that citizen and civil society data can play as an advocacy tool to shape institutional data collection practices. In that spirit, the aim here is to provide not a final product but the basis for discussion, experimentation and iterative improvement, that we hope will help to prepare the way for a global database that is maintained by an international public body in the longer term.

To that end, we would like to experiment assembling and aligning data that has been published in accordance with various existing CBCR standards and publishing requirements. This may be used to construct an open, online database into which researchers and other actors can enter new data as it becomes available, and which has the potential to become a longer term global repository for public data about the tax contributions and economic activity of multinationals, and a useful resource for future research and policy analysis. The proposed database could contain and support a range of different tools and indicators, in order to facilitate different forms of analysis and comparison across companies and across jurisdictions. This would represent an important step towards understanding the role of multinationals in the composition of the world economy – as well as paving the way for an official public database.

The purpose of creating a database would extend beyond that of a technical project to simply gather and publish existing information. There are other things that we might expect a global civil society database to do. As economic sociologist Donald MacKenzie argues, economic models can be considered not just cameras which represent the world, but also as engines which change them in different ways (MacKenzie, 2008). By taking steps to render the economic activities and tax contributions of multinationals publicly visible, measurable, quantifiable and accountable, it might be expected to change not only the dynamics of corporate reporting (as one might expect), but potentially also the operations and organisation of multinational firms as they adjust to new forms of publicity and public engagement.1 The behaviour-changing effects of public data on the economic activities and tax arrangements of multinationals are certainly deserving of further attention and research.

A public database could potentially play a social function in assembling and facilitating collaboration between different "data publics" interested in multinational taxation. It would thus represent an experiment in socio-technical design to organise public activity around tax base erosion. As well as supporting links between relevant data projects such as OpenCorporates,2 Open Ownership,3 the Open Contracting Partnership4 and OpenOil,5 it could act as a locus to coordinate the efforts of different actors and groups who are interested in undertaking research, journalism, advocacy, public policy, and public engagement work in the service of building a fairer global tax system. This would not simply be a matter of catering to pre-existing social groups, but also potentially creating new kinds of associations and collaborations between different actors. As such a public database could also be viewed as a democratic experiment – especially if these different groups play not only a role not only in using and consuming data, but also in co-designing and assembling the database (Gray, 2016a, 2016b). Such a database might thus open up space for new kinds of democratic deliberation and public engagement around how the global economy is organised – and how some of the largest most powerful economic actors on the planet - both multinationals and jurisdictions including major tax havens - can be understood, managed and held to account; as well supporting civil society interventions around the kinds of transparency measures and data collection processes we have in place to understand and shape the behaviour of these actors.

-

In terms of reporting, many banks providing data under CRD IV now also publish a statement of tax policy, e.g. Rabobank: https://www.rabobank.com/en/images/rabobank-tax-policy-statement-annual-results-2015.pdf. Until full CBCR is public, behavioural changes are less obvious, although forthcoming work from Oxfam and SOMO may demonstrate interesting effects of CRD IV reporting. Anecdotally, there is broad consensus. ↩

-

https://opencorporates.com ↩

-

http://openownership.org/ ↩

-

http://www.open-contracting.org/ ↩

-

http://openoil.net/ ↩

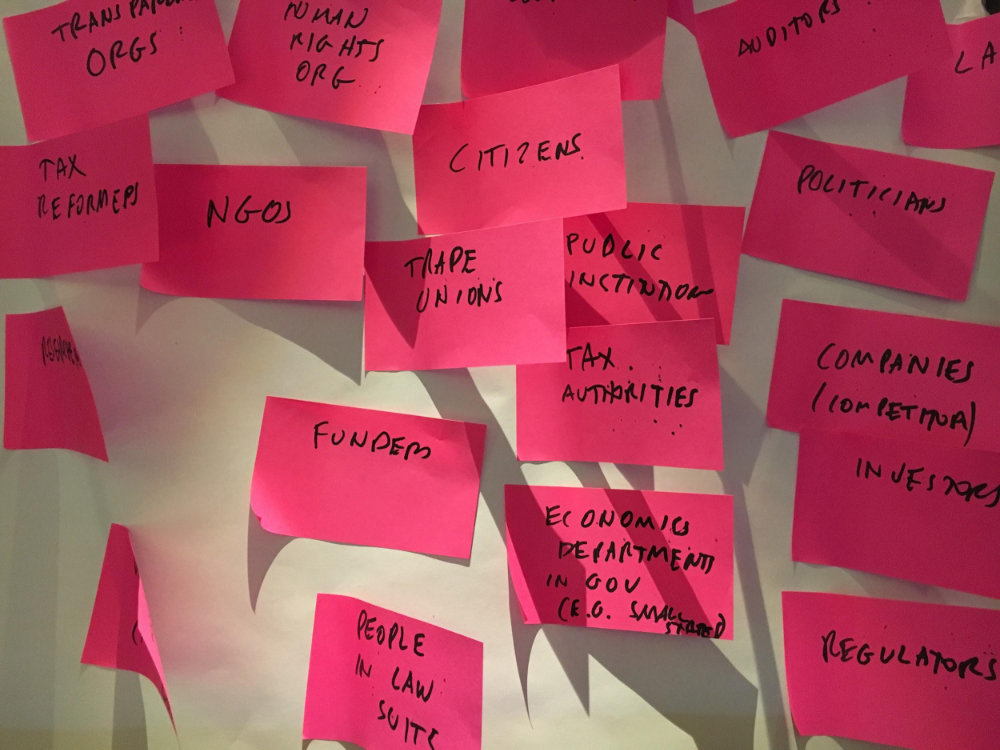

1. Who Would Use A Public Database and How?

In this section we look at the envisaged publics of a public database. Reports suggest that "a properly designed country-by-country reporting regime would be a much needed weapon for tax authorities which at present suffer from information asymmetry in the tax avoidance battle with MNEs" (Ting, 2014). But while the OECD proposals mainly focus on facilitating automatic information exchange between tax authorities, we are interested in who else could use and benefit from having access to a more comprehensive picture of the tax contributions and economic activities of multinational companies, beyond tax authorities, audit firms and the multinationals themselves.

A public database would represent a shift beyond a narrow conception of accounting for the activities of multinationals as a niche activity for professional specialists, and towards a vision which sees a broader range of actors involved in witnessing the tax arrangements of multinationals and engaging in a range of activities to hold them to account.

In order to better understand the prospective users and scenarios of use of a public database, we solicited for input in the form of "user stories" from a network of people and organisations associated with the Open Data for Tax Justice initiative. User stories are widely used as a technique to gather user requirements for agile software development (Cohn, 2004). They are often written in the form “As a [user], I need/want/expect to [need], so that [motivation]”.

An initial set of user stories were created by a group at a participatory design workshop in Oxford in October 2016, and refined and developed with further input received online in response to a public call and outreach to prospective users. These user stories, questions and analytical requirements are intended to serve as input to subsequent design and development activities, and to evaluate the opportunities and limitations of a database assembled through the repurposing of existing sources of public information. We are reproducing them below in order to illustrate the range of envisaged publics and interests around a future database.

Citizens and Civil Society Groups

List of potential questions and queries from citizens and civil society organisations:

- Who is in my country?

- What do they do here?

- How many people do they employ?

- Do multinational companies make profits in my country?

- If so, do they pay tax?

- Does my country’s tax rate seem odd compared to other countries?

- How much has a multinational got invested in my country?

- How much tax are shops in my high street paying and/or avoiding?

- Which companies are avoiding tax in my country?

- How is my country facilitating tax avoidance?

- What are the addresses of subsidiaries of a given corporate group?

- Will I be able to compare different companies within a sector across all countries consistently?

- How much profit is declared by mining and petroleum companies in countries where resources are extracted? In other countries? In tax havens?

Journalists and Media Organisations

List of potential questions and queries from journalists and media organisations:

- What companies does a corporate group own within a country?

- Who owns a given company?

- What does a group do in a country?

- What are the profits per employee in a given country?

- What are the sales per employee in a given country?

- How do profits per employee vary across countries?

- How do sales per employee vary across countries?

- How do rates of profit per employee vary over time and across countries?

- How do rates of sales per employee vary over time and across countries?

Researchers and Academics

List of potential questions and queries from researchers and academics:

- What are the drivers of international trade and investment structures?

- What is the relationship between the "real" and paper global economy?

- Is there base erosion and profit shifting?

- What role do low tax jurisdictions have to play in a group?

- What is the cost of tax havens to society?

- Are there patterns of behaviour that appear to be repeated between corporate groups and what do they imply?

- Is there evidence that the behaviour of a corporate group might be impacted by the advisers that it engages?

- Why have groups changed their behaviour?

Companies and Investors

List of potential questions and queries from companies and investors:

- What are the effective tax rates in a given sector in different countries?

- Do taxes paid/accrued and profits before tax tell a consistent story?

- Do the outputs make sense when benchmarked against past performance?

- Are consistent results achieved across similar entities in the group?

- If there are inconsistent results between group companies does this suggest that some activities should be closed and the capital used be reallocated?

- Is the CBCR headcount consistent with other reportable information and taxable status per jurisdiction?

- Can the CBCR data be reconciled to other local reporting?

- Are the outputs of the CBCR in line with transfer pricing policies (and is the policy consistent)?

- Are there anomalies in the CBCR data that may need correction or explanation?

- Could the outputs of the CBCR lead to tax audit or reputational risk?

- Are companies living up to their claims?

- What geopolitical risks exist within the group?

- Does the company face governance risk because of the complexity or artificiality of its group structure?

- Does the company face risk of consumer or other boycotts because of the nature of its supply chains or spread of its activities?

- What is the overall level of risk I should attach to this company and does this change its weighting in my portfolio?

- Does this company appear to fail our ethical investment criteria?

- Does this company trade in places with unacceptable ethical risk?

Public Institutions and International Organisations

List of potential questions and queries from public institutions and international organisations:

- What is the scale of multinational tax avoidance in our country?

- How does multinational tax avoidance in our country compare to others?

- Which are the most aggressive tax avoiders in our country?

- Are companies complying with their reporting obligations?

- What are the effective tax rates in a given country - by company, or by sector?

- What are the tax contributions of companies that we contract or fund?

-

See: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/local-councils-should-vet-suppliers-for-tax-avoidance-charity-says-a6799961.html ↩

2. What Should A Public Database Contain?

Having examined some of the aspirations and envisaged scenarios of usage for a global public database in the previous section, in this section we look at different proposals for what information could and should be contained within it. Firstly we compare different proposals for "Country-by-Country Reporting" (CBCR). Secondly we look at other sources of information that could be contained within a public database – and the kinds of analytical operations that this information would facilitate.

Country-by-Country Reporting: Civil Society Proposals and the OECD Standard

Some early proposals for public CBCR (Murphy, 2003; and e.g. 2012) suggest a broad accountability mechanism for both multinationals and tax authorities. Multinationals’ licence to operate in a given jurisdiction and globally depends on meeting their tax responsibilities, and upon being able to publicly account for having done so. The resulting data provides the public and policymakers with the basis for important economic decision-making. In addition, it will demonstrate alignments and misalignments – in respect of companies, and of jurisdictions – between the location of activity, and the extent of declared profits and tax.

Comparing the civil society proposals with OECD standard

| Civil society proposals | OECD CBCR | |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | All multinationals | Group revenue ≥ €750 million |

| Identity | Group name | Group name |

| Countries in which the Group operates | Countries in which the Group operates | |

| Full list of the nature of activities in each country | Full list of the nature of activities in each country | |

| Names of constituent companies trading in each country | Names of constituent companies trading in each country | |

| Activity | Third party sales from each country | Third party sales from each country |

| Intragroup sales from each country | Intragroup sales from each country | |

| Total sales from each country | Total sales from each country | |

| Number of employees FTE | Number of employees FTE | |

| Total employee remuneration | ||

| Investment in tangible fixed assets | Total capital employed split between committed capital and retained reserves | |

| Intra-group transactions | Intra-group sales – stated by both source and destination if the two differ by more than 10% for any jurisdiction | |

| Intra-group purchases | ||

| Intra-group royalties rec'd | ||

| Intra-group royalties paid | ||

| Intra-group interest rec'd | ||

| Intra-group interest paid | ||

| Key financials | Profit or loss before tax | Profit or loss before tax |

| Payments to/from governments | Current tax accrued | Current tax accrued |

| Tax paid | Tax paid | |

| Any public subsidies received |

The civil society proposals for CBCR data therefore cover four main areas:

-

Firstly there is identity: which is the multinational group to which the data refers, in which jurisdictions it operates, and under what names (e.g. those of subsidiary or branch entities) it is known in that place.

-

Secondly there is activity: what is the scale of the group’s sales, assets and employment for each jurisdiction of operation7.

-

Thirdly there are intra-group transactions: in order to understand the real patterns of activity and profitability and how these are influenced by transactions within a group we need to know what are the intra-group components of sales and purchases, of royalties received and paid, and of interest received and paid. In addition, because sales can, of course, be made both from and to a place it can be important to know figures for both if they are materially different for a location8.

-

Fourthly there is key financial data: what are the levels of declared profit or loss before tax, and of tax accrued and paid. (See also detailed discussion of data fields in section 3.)9

When the OECD was mandated to create a CBCR reporting standard in 2013, it followed closely the civil society proposals that had led to that mandate. The omissions and variances from the ultimate standard fall in three areas. In activity, the OECD standard includes employee number but omits payroll costs. It was argued that payroll information was too sensitive to disclose in some locations where there were few employees. In intra-group transactions, the OECD standard includes sales but omits purchases, royalties and interest. The ultimate standard would like to know tangible asset investment: the OECD uses a financial capital approximation instead. The table above summarises these differences. One notable issue where agreement was secured from the OECD despite considerable opposition was that the data must be made available for all jurisdictions in which a multinational corporation has an operation: it was claimed by many who made representation that this was unnecessary and only larger jurisdictions need be disclosed. These representations ignored the fact that this would have continued to hide almost all tax haven usage and that intra-group transactions are rarely included in assessments of materiality. Agreement from the OECD on this issue was vital for the securing of meaningful CBCR data in the long term.

A big shortfall with the OECD standard, explored in section 3, is the availability of the data. Two major setbacks occurred during the negotiations of the OECD BEPS process (the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting action plan that took place from 2013-2015). First, the requirement to make data public was replaced by a requirement to provide data privately to tax authorities. Second, that requirement was narrowed further, so that data would be provided only to the tax authority in a multinational group’s headquarters jurisdiction. This in turn necessitated the complex and ongoing creation of a structure for exchange of CBCR information between tax authorities.

One particularly damaging result is a systemic bias against lower-income countries in access to information. The evidence suggests that OECD countries lose 2-3% of their total tax revenues to multinational profit-shifting, compared to 6-13% in lower-income countries (Cobham & Gibson, 2016, based on Crivelli, de Mooij & Keen, 2015). The OECD-imposed hurdles to receiving CBCR information act to exacerbate the inequality in global taxing rights, as detailed in Knobel & Cobham (2016). A third issue is the relatively high turnover threshold for reporting MNEs (€750m annually), and may also introduce a systematic bias, if as seems likely lower-income countries have a higher share of their MNE operations carried out by smaller MNEs.

The map below illustrates the problem of unequal access to the agreed data. Highlighted are those countries which are eligible, as of August 2015, to receive CBCR data from participating tax authorities (which, recall, are the headquarters countries of multinationals and so predominantly OECD countries themselves). The picture remains challenging for lower-income countries (Knobel and Cobham, 2016).

The hurdles to information access are two: countries must be signatories to the Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement (CBC-MCAA) for automatic exchange of information based on Article 6 of the Multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters;10 and have undergone the "peer reviews" of the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes and been found to be “compliant,” “largely compliant” or “partially compliant” with the confidentiality standard.11

Some lower-income countries have taken sensible steps to undermine the OECD restrictions, by legislating for direct local filing of CBCR. In practice, however, the balance of power between tax authorities and MNEs means that this may be easier for China to enforce than, say, Malawi.

Signatories of Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement (CBC-MCAA) and compliance with the confidentiality standard, EY, August 201512

The major accountability channels supported by CBCR rest, ultimately, on the public availability of data. This also supports combination with a range of other data types, including both contextual information about jurisdictions, and a range of related information about multinational groups and their networks and activities.

Beyond Country-by-Country Reporting Data?

While country-by-country reporting information would constitute a central and vital part of a global public database, other further information might be added in order to address some of the interests and concerns that were surfaced through the user stories and participatory design activities mentioned in the previous section – from journalists and civil society organisations wishing to examine tax avoidance claims in relation to local economic activity, to researchers wishing to layer different kinds of information in order to contextualise CBCR data with information on GDP, population or other types of economic data. Here we discuss two areas of information which issue from the user stories: company information (including beneficial ownership data), and additional contextual information.

Beneficial Ownership and Other Company Information

While CBCR data would give users of a global database a good overview of the tax contributions and economic activities of a multinational, it would not in itself enable them to understand the structure and composition of a corporate group. For this, further company information would be required, including who really owns and controls a given legal entity, and how, which would reveal the structure of corporate groups by providing so-called "beneficial ownership" data, as well as other kinds of information about its operations.

The request for public registers of the beneficial ownership of companies, trusts and foundations was one of the three main proposals in the platform set out by TJN after its establishment in 2003 (Murphy, Christensen & Kimmis, 2005). Over the past few years there have been a number of civil society initiatives asking for beneficial ownership information to be collected, and to be made public (cf. Gray & Davies, 2015). Multiple jurisdictions have now begun to introduce public registers of the beneficial ownership of companies, including a range of commitments from Afghanistan and France to the Netherlands and Nigeria at the London Anti-Corruption Summit in May 2016; and a pan-EU initiative through the revision of the Anti-Money Laundering Directive.

The result of these initiatives, and additional voluntarily provided information, will be brought together over in a new Global Beneficial Ownership Register (Hussain, 2016). This will combine through the CBCR identity information to extend substantially the knowledge of multinational networks. Similarly, data from registers with related information such as the UK’s Companies House will allow the combination of CBCR with data including company accounts. Journalists, researchers and civil society groups have begun to explore and experiment with this newly available information,13 and there are many opportunities to build stronger connections between this and policy, advocacy and research work around the tax contributions of multinationals.

Additional Contextual Information

In addition, it may be possible to combine partially aggregated country-by-country data. There are national surveys of multinationals headquartered in the USA, Germany and Japan, of which some statistics are made public. In the USA case at least, this provides the basis for broad analysis of the pattern of global profit shifting (e.g. Cobham & Janský, 2015; Clausing, 2016). Where these are comprehensive, they may provide the ‘frame’ into which more detailed individual CBCR data fits - for example, to understand the proportion of the activity of US multinationals in a given country for which CBCR data is available.

Further contextual information may also be brought in. This could include data on stocks and flows of foreign direct investment - for example, from the UNCTAD database and/or the coordinated (direct and portfolio) investment surveys of the IMF; on international investment positions and national balance of payments data (IMF); on bilateral banking positions (BIS); and on trade flows (UNCTAD, IMF).

In terms of broader context for understanding the scale and intensity of multinational activity, national-level data could also be included on, for example, GDP, population, labour force (e.g. World Bank and ILO) and of course tax revenues (e.g. ICTD-WIDER Government Revenue Dataset).

-

Additional data on the type of activities in a given jurisdiction is also provided by some banks under CRD IV (e.g. Unicredit and Intesa Saopaolo), and could provide valuable detail for wider CBCR too. As in other cases (see chapter 3), this would raise issues of standardisation among reporting companies. ↩

-

Additional possibilities here include intra-group dividends and intra-group derivatives, both also used in profit-shifting. ↩

-

An additional possibility here is deferred tax. ↩

-

See: https://www.oecd.org/tax/automatic-exchange/about-automatic-exchange/cbc-mcaa.pdf ↩

-

See: https://www.oecd.org/tax/transparency/exchange-of-information-on-request/ratings/#d.en.342263 ↩

-

https://webforms.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-country-implementation-of-beps-actions-8-10-and-13-august-2015/$FILE/ey-country-implementation-of-beps-actions-8-10-and-13.pdf ↩

-

See, e.g. https://www.globalwitness.org/en-gb/blog/what-does-uk-beneficial-ownership-data-show-us/ ↩

3. What Are the Prospects of a Public Database from Existing Information Sources?

In this section we look at the extent to which a public database might draw on publicly available data from different sources – by examining different reporting requirements that mandate the collection and publication of the kinds of data that were discussed in the previous section. We start with an overview of how different data sources compare to civil society and OECD standards for Country-by-Country Reporting. Then we go on to look at the current state of national implementations of OECD standards in different countries and regions. Finally we take a closer look at public data from sector specific disclosure rules and voluntary disclosures.

How Do Corporate Disclosure Rules Measure Up to Civil Society and OECD Standards?

There are now multiple country-by-country reporting standards, for both public and private data and with significantly varying scope and specificity.14 This is both a testament to the success of civil society advocates, and a challenge for the effective use of the resulting data.

Part of the motivation for the current project is to respond to this challenge by looking at ways of assembling and aligning CBCR data, and bringing them together alongside other data sources and associated tools. At the same time, the database has the potential to reduce reporter compliance costs (see Cobham, 2014). In this section we consider the likely availability of data in respect of the various standards.

The table below provides an overview of the data fields available under each standard. Cells in green indicate that a standard includes the ‘ideal’ data field. Cells in yellow indicate a related but not fully equivalent field; while cells in red indicate an absence of the field. Three points stand out. First, as noted above, the OECD standard’s omissions relate to activity and to intra-group transactions. This restricts quite seriously the types of questions that can be addressed. Second, the CRD IV standard for public CBCR by EU financial institutions has broadly similar data fields to the OECD standard. Third and perhaps most striking is the extent of omissions across the series of extractive sector standards (as we shall discuss further below).

-

For one recent industry analysis, see KPMG (2016). ↩

Comparison of data fields in CBCR standards

Identity

| Civil society proposal | OECD CBCR | CRD IV | Dodd Frank | Canada | EITI | EU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group name | Group name | Group name | Group name | Payee name | Payee name | Group name |

| Countries | Countries | Countries | Countries | Countries | Legal and institutional framework | Countries |

| Nature of activities | Nature of activities | Nature of activities | Projects (as in: by contract) | Same data required per project as well as per country | Allocation of contracts and licenses | Projects (as in: by contract) |

| Names of constituent companies | Names of constituent companies | Receiving body in government | Subsidiaries if qualifying reporting entities | Exploration and production |

Activity

| Civil society proposal | OECD CBCR | CRD IV | Dodd Frank | Canada | EITI | EU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Third party sales | Third party sales | Social and economic spending | ||||

| Turnover | By the process of addition | Turnover | ||||

| Number of employees FTE | Number of employees FTE | Number of employees | ||||

| Total employee pay | ||||||

| Assets? |

Intra-group transactions

| Civil society proposal | OECD CBCR | CRD IV | Dodd Frank | Canada | EITI | EU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-group sales | Intra-group sales | |||||

| Intra-group purchases | ||||||

| Intra-group royalties rec'd | ||||||

| Intra-group royalties paid | ||||||

| Intra-group interest rec'd | ||||||

| Intra-group interest paid |

Key financials

| Civil society proposal | OECD CBCR | CRD IV | Dodd Frank | Canada | EITI | EU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profit or loss before tax | Profit or loss before tax | Profit or loss before tax |

Payments to/from governments

| Civil society proposal | OECD CBCR | CRD IV | Dodd Frank | Canada | EITI | EU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tax accrued | Tax accrued | |||||

| Tax paid | Tax paid | Tax paid | Income taxes paid | Tax paid | Profits taxes | taxes levied on the income, production or profits of companies |

| Any public subsidies received | Any public subsidies received |

The OECD Standard: National and Regional Implementations

As is typically the case with changes to the OECD’s international tax rules, implementation of the standard has been rapid and widespread. While the standard sticks relatively closely to significant elements of the civil society proposals, the question of interest is whether the information will be made public. In this regard, there are ongoing processes and political discussions in multiple jurisdictions.

The most important, in terms of potential coverage as a share of the global activity of multinationals, is the process at EU level. While MEPs and committees of the European Parliament have tended to support publication of OECD standard CBCR, the European Commission in April, 2016 brought forward a more limited proposal. The Commission (EC, 2016) proposes to limit the data fields to be made public, and also to aggregate reporting for all non-EU jurisdictions except certain ‘tax havens’. They noted that:

Public reporting does not serve the same purpose as information sharing and reporting between tax authorities. There are some types of information that are required to be shared between tax authorities, but that are not part of this latest proposal for public CBCR. EU tax authorities will receive 12 pieces of information [under implementation of the OECD standard], whereas public CBCR will consist of just seven pieces of information. EU tax authorities will receive more granular data for all third countries in which an EU company is active. They will also get from companies more complex data relating to the breakdown of a group's turnover between that made with external parties and that made solely between group entities, as well as figures for stated capital and a company’s tangible assets.

When it comes to public disclosure, it is important that EU citizens get information about where in the EU companies are paying taxes. Citizens also have a legitimate interest in knowing whether companies active in the EU are also active in so-called tax havens. However, demanding publicly disaggregated data for all third countries could affect companies' competitiveness and divulge information on key strategic investments in a given country. Similarly, the disclosure of turnover and purchases within a group poses a threat to multinationals in that it could divulge key information to competitors.

Civil society groups (e.g. ActionAid et al., 2016) have pointed out the inconsistencies in this argument. The basis for the proposed exclusions, both of a number of the data fields and of reporting for (most) non-EU jurisdictions, would apply equally to the EU’s extant public CBCR standards for financial institutions and the extractive sector. It is at best unclear why any of the Commission justifications fail to apply, or apply differently, in those sectors. In addition, the logic applied assumes that CBCR data is only of interest for tax purposes. This is not the case: the interest is much broader and CBCR should be considered to be accounting and not tax data as a result (Murphy, 2003 and 2012).

Discussions on publication of CBCR data are also ongoing in a range of EU member states. In France, MPs voted for public OECD CBCR, before the government managed to reverse the vote using a technicality. In the UK, the government agreed in September 2016 an opposition amendment to provide Treasury with the power, but not the obligation, to require public OECD CBCR. In addition, a number of governments have indicated their support for public OECD CBCR including the UK, which prompted supportive discussions at the Council of Ministers in February 2016,15 and the Netherlands, which recently released a letter in support.16

While data is still lacking, it may be that a majority of multinationals within the scope of OECD CBCR (e.g. with group revenues over €750m) operate within the EU. As such, an EU requirement for full publication would have global impact. Indirectly, it would also be likely to remove most of the resistance elsewhere, since for others to follow suit would simply be to level the playing field. Unilateral steps by e.g. the UK or Australia could set the path for others to follow.

While these national sources of CBCR data have the potential to be extremely valuable if they are made public, in many cases we are still waiting for data to be published.

Sector Specific Information

Extractive Industries Data

Information from extractive industries could be very useful in supporting experimentation towards a global civil society database on multinational tax contributions. Multilateral initiatives like the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) have helped to secure the disclosure of corporate data from multinationals active around the extraction of oil, gas, minerals and other natural resources.17 The EITI standard includes the disclosure of government revenues and company payments – including "comprehensive disclosure of taxes and revenues". In addition to voluntary transparency initiatives like EITI, the past few years has also seen the introduction of disclosure rules through sections of associated legislation – such as Section 1504 of the US Dodd Frank Act (which is in the process of being repealed)18, and the EU Accounting Directive.

However, there are unfortunate limitations to the data that is currently disclosed with respect to the economic activities and tax contributions of multinationals. Perhaps this partly reflects a historical focus of extractive industry transparency standards on holding corrupt governments to account, rather than looking at the transnational tax affairs of multinationals. Extractive industries transparency was often framed as one of governments failing to pass the benefits of large extractive contracts on to citizens. These standards therefore share common omissions: there is little or no data on companies’ activity, intra-group transactions or profitability. The data on payments made is intended to allow comparison with public finances, to support government accountability - but not with any denominators that support corporate accountability. When used in combination with other contextual data – such as production volumes, prices and costs – extractives payment data can contribute to understanding whether or not companies are depriving governments of public revenues. But its value in relation to obtaining a more joined up picture of the tax affairs of multinationals remains limited. There are currently efforts to combine public CBCR with the specific rules for the extractive industries, in order to overcome these deficiencies. This makes it important to note the specific information requirements of this sector when considering the more general demand for public CBCR data.

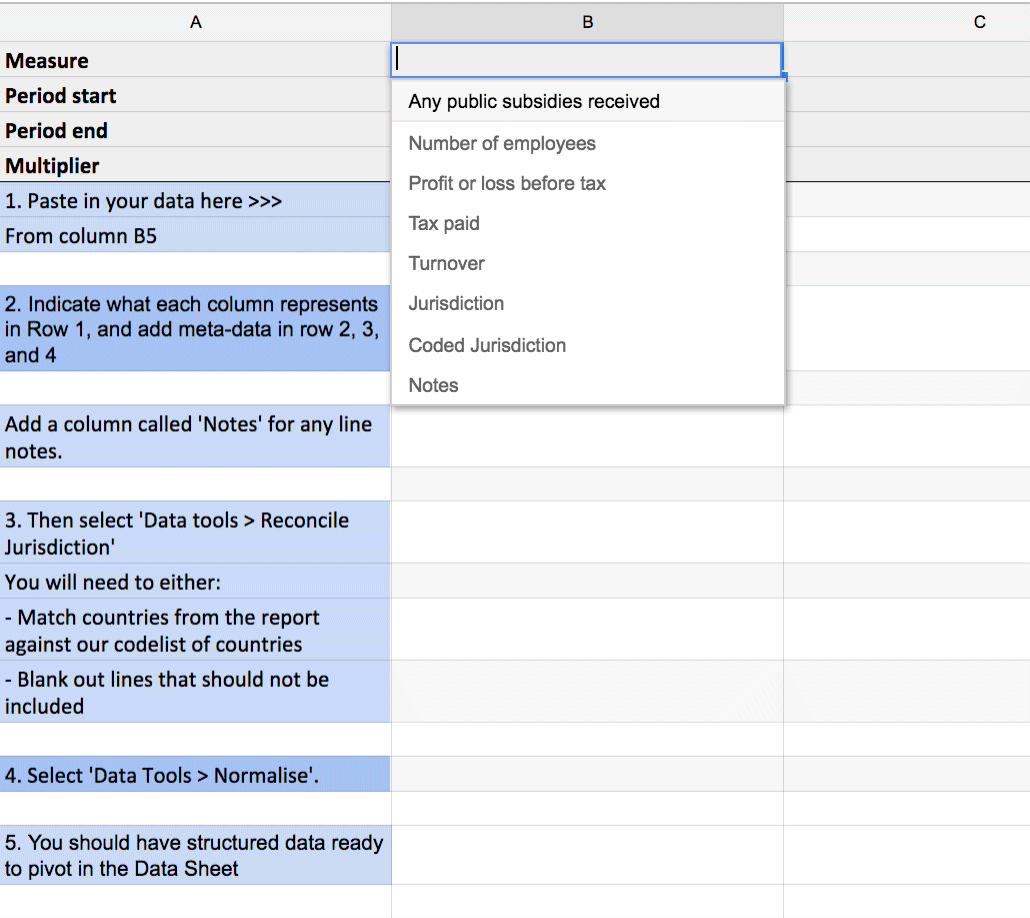

Financial Institutions

Another area where sector specific transparency initiatives could provide information for a global database is around financial institutions. For example, the EU Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV) requires the disclosure of information across three of the main four areas described above, which is enough information to undertake basic analysis of the alignments and misalignments between economic activity and tax contributions. Given that this was at the time of writing the best available source of "good enough" CBCR data, we decided to explore issues related to gathering it into a public civil society database. Below we discuss some of the issues that we encountered that may serve to inform further experimentation in this area.

Firstly there is an issue related to the discoverability of CRD IV data. Companies are required to make this information available, but there is currently no central point of reference or official aggregation mechanism for CRD IV data. Instead one has to go to search for this either on the web or on the websites of financial institutions. As a test we started with several lists of the top European banks19 in order to see whether we could assemble a small pilot CBCR dataset – including at a workshop with a group of researchers, journalists, civil society organisations and open data activists, as well as with student groups at King’s College London and Charles University in Prague.20 Working from these reference lists, we devised several strategies for finding CRD IV data on company websites – including through targeted queries.

Once the relevant information is found, the next issue is machine readability. Often CRD IV is published in the context of company reports in PDF format, which means that additional work is required to extract structured data. In the workshop we experimented with several online tools to extract structured tables from reports in order to copy them into an online spreadsheet.21 As CBCR information may potentially be spread across several different reports or parts of reports, further work is required to identify and extract relevant data.

Next there are issues related to the comparability of the data. Here we encountered numerous issues, such as:

-

The lack of standardisation in the names of countries or regions (including contestation and different conceptions around what counts as a country), and/or in the degree to which subsidiaries are listed;

-

The variable use of groups of countries or regions for reporting purposes (such as "Channel Islands" or “Asia”);

-

Reporting by company rather than by country (including banks being listed in country columns, or listing multiple subsidiaries per country, which renders comparison more difficult);

-

The extensive use of "other" sections to describe different aspects of the operations of a group in a way which was not comparable;

-

The use of different currencies;

-

Different descriptions and uses of similar metadata fields (which may carry slightly different meanings, depending on the financial processes and context of the company or group);

-

Missing and blank values; and

-

Lack of explanation where CBCR totals do not reconcile to consolidated group statements.

In order to mitigate some of these issues, we created a basic protocol for collecting and verifying data, based on the extraction of structured data, and the reconciliation of data fields with various relevant international standards (such as ISO standards for countries and currencies); units (e.g. thousands or millions); as well as reference fields (e.g. number of employees, tax paid, turnover, etc).22 Through this process we wanted to facilitate a basic level of "data work" to harmonise the data we could obtain, whilst also keeping track of provenance (e.g. original URLs) and differences (e.g. fields that were reported by some multinationals and not others), and versions (e.g. original labels and metadata descriptions, original currencies, etc).

Template spreadsheet for collecting structured data from PDF reports.

Template spreadsheet for collecting structured data from PDF reports.

This exercise serves to highlight some of the different issues that would likely be encountered in the assembly of a civil society database. As alluded to above, it also suggests that the purpose would not simply be to assemble and provide the best available public information about the economic activities and tax contributions of multinationals. A database could also serve to highlight what campaigners, civil society groups, public institutions and policy-makers can learn about the information about multinationals which is disclosed through various kinds of disclosure initiative. Furthermore it could also facilitate the coordination and documentation of different kinds of collaborative "data work" between diverse actors who share an interest in this information – which one of us elsewhere describes as a “participatory data infrastructure” (Gray & Davies, 2015).

Voluntary CBCR Information

One more source of CBCR information (and other associated information about multinational tax contributions and economic activity) is through voluntary disclosures. Multinationals such as Barclays and Vodafone have previously published CBCR data as part of transparency and corporate responsibility initiatives. For example, upon publishing their CBCR data, Barclays wrote:

Bank taxation remains a matter of some public interest, and we believe that Barclays should take a lead in explaining our activity transparently so that we can engage with all our stakeholders on an informed basis.

This may be a growing source of information, as multinationals decide to pursue proactive disclosure in order to reassure investors, shareholders, customers, media and other publics about their tax status – both to demonstrate leadership around an area of growing ethical and political concern, as well as to address concerns about risk from tax minimisation strategies. Preliminary exploration of such voluntary data has shown that data is often reported in different ways, and sometimes only partially – with geographical or other omissions.23 Thus while it is an important source of data, we suspect that there is not yet enough comparable data to be used as the basis for a pilot database.

-

See: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2016-02-23/debates/16022347000006/ECOFIN12February2016 ↩

-

See: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/binaries/rijksoverheid/documenten/kamerstukken/2016/10/19/tk-motie-merkies-over-country-by-country-reporting/tk-motie-merkies-over-country-by-country-reporting.pdf ↩

-

See: https://eiti.org/ ↩

-

See: https://politicsofpoverty.oxfamamerica.org/2017/02/thank-you-to-the-187-members-of-the-house-and-47-senators-who-voted-against-corruption/ ↩

-

Such as: http://www.relbanks.com/top-european-banks/assets ↩

-

Thanks to Petr Janský at Charles University; Tommaso Venturini and Liliana Bounegru at King’s College London; and to all of their students for contributing to these experiments in data collection, exploration and analysis. ↩

-

Such as: https://pdftables.com/ ↩

-

Thanks to our colleague Tim Davies of the Open Data Services Co-operative for creating the initial template Google Spreadsheet at the workshop in Oxford. ↩

-

See, for example: http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2015/12/21/vodafone-has-a-long-way-to-go-before-it-is-doing-country-by-country-reporting/ and https://www.home.barclays/content/dam/barclayspublic/docs/Citizenship/Reports-Publications/CountrySnapshot.pdf ↩

4. What Are the Next Steps?

In sections above we have looked at different conceptions of who would use a public civil society database and what they would use it for; different proposals for what such a database should contain; and different existing and forthcoming information sources which could be used to seed and populate a prototype database. In this final section, we conclude with a series of reflections, recommendations and suggestions for next steps.

Building a Pilot Civil Society Database

Based on our analysis in the previous section, we’d suggest the creation of a pilot civil society database drawing on CRD IV data in the first instance. Here one may draw on the emerging craft of designing and assembling socio-technical infrastructures to facilitate collaborative "data work", including the creation, assembly and use of public data – from data journalism projects such as the Guardian’s The Counted24 or The Migrants Files;25 to civil society projects such as OpenStreetMap,26 OpenSpending,27 OpenTrials28 or a growing number of citizen data projects repurposing “born digital” data from devices or platforms to advocate for changes in what is officially counted (Gray, Lämmerhirt, & Bounegru, 2016). As suggested above, CRD IV data is the closest to civil society and OECD recommendations, and there are already several years of data available to experiment with. It also poses a set of challenges related to discovery, machine readability and comparability which may also occur in relation to other relevant areas of data collection and publication.

In particular, the CRD IV data might be used to experiment with designing processes to assemble and align data – including through crowdsourcing mechanisms, and features designed to facilitate collaboration such as version control and verification processes (to track provenance and check changes and additions to the data). The user stories that we have collected may serve as one starting point for the development of a pilot database, along with further research and testing. The user of participatory design and agile development methodologies may help to iteratively develop a pilot database in close collaboration with its users. Further development could proceed by identifying common ground between the most recurring and prominent analytical requirements and what is possible given the various limitations of existing CRD IV data. We suggest that particular attention should be paid to how the database might facilitate the assembly, collaboration and coordination between different "data publics" of multinational tax information.

While CRD IV data would serve as a good basis for an initial experimentation, the pilot should also be accompanied by further exploration of data issues in other fields – such as extractives transparency data, voluntary disclosures, the publication of national or regional OECD standard CBCR data, newly available beneficial ownership information, as well as other publicly available sources such as the ICIJ’s Panama Papers and Luxembourg Leaks data.29 This may include small scale initiatives in data collection and alignment, as well as in linking, connecting and reconciling different kinds of data. In the medium term, learning from the data issues across these different regions and sectors will help to inform the development of a civil society database which can accommodate and help to organise, keep track of and facilitate the analysis and use of heterogeneous types of information about multinationals from different sources.

A pilot database around CRD IV would provide opportunities for seeing what can be learned both from the data and about the data. On the one hand it would provide an unprecedented picture of the economic activities and tax contributions of multinational financial institutions with operations in Europe. On the other hand it would serve to highlight limitations and issues with CRD IV data, which in turn would suggest what is – and is not – currently possible to ascertain on the basis of this data, as well as feeding into ongoing efforts to shape what data is collected and reported.30

Further Advocacy, Policy and Research Work

In addition to creating a pilot civil society database, what else can be done? The three sections above suggest future directions for advocacy, policy and research work.

In relation to question of who would use the database and for what, further work could be done to identify, engage with and understand the needs of other potential users of a public database. The user stories are suggestive of how a variety of practitioners envisage the different "data publics" of a civil society database, but further work could be done to obtain a more granular picture of who might be interested in multinational tax data. One approach to this would be to build on existing research (e.g. Seabrooke & Wigan, 2016) to map the different actors with an interest in multinational tax. This could follow a similar approach to previous research to map “issue publics” and “data publics” in other areas, such as around budget data (Gray, 2015; cf. Rogers, 2013). Further research could also provide a richer picture of analytical interests around the data (cf. De Renzio & Simson, 2013), as well as how the database would feature in the different workflows and settings of different actors who would use it. Of course, a pilot database would also help to compare the interests of envisaged or imagined users with actual users.

In relation to the question of what should be included, arguably the biggest priority is policy and advocacy work to support public CBCR data released in accordance with the civil society and OECD proposals. The current frontier is ongoing work around the national and regional implementation of these proposals. Collaboration around transparency rules, norms and practices across sectors and data types (e.g. natural resource transparency, open contracting, public spending data and beneficial ownership transparency) may also help to expedite convergence and consensus around common standards and disclosure rules, as well as creating opportunities for other data sources which may be added to a global database. As well as bridging between policy and advocacy work around tax justice and other transparency areas, there may also be opportunities to build on global momentum for open data - from the UN’s "data revolution" and the emphasis on data in relation to the Sustainable Development Goals, to open data initiatives around the world – such as the activities of intergovernmental organisations such as the World Bank; transnational and multilateral fora and initiatives like the Open Data Charter, the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI), the Open Government Partnership (OGP) and the European Union’s open data initiative; as well as national, regional and local open data initiatives around the world.

Finally, in relation to the the question of how data should be published, from the previous section it is clear that researchers, practitioners, policy-makers, public institutions and civil society groups should work together to push for data which is discoverable, reusable, machine-readable and comparable. This may include collecting and publishing machine-readable data through a single point of reference on official websites, rather than publishing data as part of existing company reports in PDFs scattered across the web. In accordance with open data principles, information should also be published using open licenses in order to facilitate re-use.31 The more substantive challenge is alignment around common definitions, standards, identifiers data practices – which will entail the creation and adoption of shared understandings of countries, companies, currencies and other elements that will be included in the database. Here we may heed recent calls for convergence around unique identifiers (e.g. Davies & Gower, 2016). This may entail changes not only in how data is published, but how it is created by multinationals in the first place. As with all shared practices of classification and standardisation, this will entail not only technical, but also social and political work (cf. Bowker & Star, 2000). The nature and focus of this social and political work may be determined by further study of not only how relevant data is currently created, but also an engagement with ongoing national and international efforts to create common data infrastructures, shared standards and reference lists that cut across different domains of data creation and use.32 These should be considered not just in terms of technological innovation, but also in terms of broader public deliberation and engagement around what public data infrastructures should do.

We hope progress in each of these areas will continue to be advanced through collaborations between tax justice campaigners and open data advocates – as well as associated journalists, researchers and practitioners – as we have sought to facilitate through the Open Data for Tax Justice Initiative which has made this report possible.

-

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2015/jun/01/the-counted-police-killings-us-database ↩

-

http://www.themigrantsfiles.com/ ↩

-

https://www.openstreetmap.org ↩

-

https://openspending.org/ ↩

-

See: http://opentrials.net/ and also Goldacre & Gray, 2016. ↩

-

See: https://panamapapers.icij.org/ and https://www.icij.org/project/luxembourg-leaks/explore-documents-luxembourg-leaks-database ↩

-

It is worth noting that CBCR data alone would not provide conclusive evidence that a company is avoiding taxes, nor to provide a conclusive answer to questions such as "Which companies are avoiding tax in my country?" that were raised in the user story section. ↩

-

See: http://opendefinition.org/ ↩

-

See, for example, UK government activities in these areas, such as: https://data.blog.gov.uk/category/data-infrastructure/ and https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/registers/registers ↩

References

ActionAid, Eurodad, Financial Transparency Coalition, Open Society European Policy Institute, ONE, Oxfam and Transparency International (2016). European Commission Proposal on Public "CBCR": Questions and Answers. Available at: http://www.transparencyinternational.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/EC-CBCR-QA-final_branded.pdf.

Bowker, G. C., & Star, S. L. (2000). Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cobham, A. (2014). Post-2015 Consensus: IFF Assessment. Copenhagen Consensus Center. Available at: http://copenhagenconsensus.com/publication/post-2015-consensus-iff-assessment-cobham

Cobham, A. & Gibson, L. (2016). Ending the Era of Tax Havens: Why the UK Government Must Lead the Way. Oxfam Briefing Paper. Available at: http://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/publications/ending-the-era-of-tax-havens-why-the-uk-government-must-lead-the-way-601121.

Cobham, A., & Janský, P. (2015). Measuring Misalignment: the Location of US Multinationals’ Economic Activity Versus the Location of their Profits. International Centre for Tax and Development Working Paper Series 42. Available at: http://www.ictd.ac/publication/2-working-papers/91-measuring-misalignment-the-location-of-us-multinationals-economic-activity-versus-the-location-of-their-profits.

Cobham, A. and Klees, S. (2016). Global Taxation: Financing Education and the Other Sustainable Development Goals. New York: International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity: http://report.educationcommission.org/download/817/.

Cohn, M. (2004). User Stories Applied: For Agile Software Development. Boston: Addison-Wesley Professional.

Clausing, K. (2016). The Effect of Profit Shifting on the Corporate Tax Base in the United States and Beyond. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2685442.

Crivelli, E., R. de Mooij and M. Keen (2015). Base Erosion, Profit Shifting and Developing Countries. IMF Working Paper 15/118: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2015/wp15118.pdf.

Davies, T., & Gower, R. (2016). Letting the Public in Opportunities and Standards for Open Data on Beneficial Ownership, Country-by-Country Reporting and Automatic Exchange of Financial Information. The Financial Transparency Coalition. Available at: https://financialtransparency.org/reports/letting-the-public-in/

De Renzio, P., & Simson, R. (2013). Transparency for What? The Usefulness of Publicly Available Budget Information in African Countries. Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved from http://www.odi.org/publications/7770-fiscal-transparency-open-budgets-public-finance

Goldacre, B., & Gray, J. (2016). OpenTrials: towards a collaborative open database of all available information on all clinical trials. Trials, 17, 164. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1290-8

Gray, J. (2015). Open Budget Data: Mapping the Landscape. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2654878

Gray, J. (2016a). Datafication and Democracy: Recalibrating Digital Information Systems to Address Societal Interests. Juncture, 23(3). Available at: http://www.ippr.org/juncture/datafication-and-democracy

Gray, J. (2016b). It Is Time for Institutions to Ensure Data Infrastructures Are More Responsive to Their Publics. LSE Impact Blog. Available at: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2016/10/07/it-is-time-for-institutions-to-ensure-data-infrastructures-are-more-responsive-to-their-publics/

Gray, J., & Davies, T. G. (2015). Fighting Phantom Firms in the UK: From Opening Up Datasets to Reshaping Data Infrastructures? Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2610937

Gray, J., Lämmerhirt, D. & Bounegru, L. (2016). Changing What Counts: How Can Citizen-Generated and Civil Society Data Be Used as an Advocacy Tool to Change Official Data Collection? Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2742871

Guardian (2007). Revealed: How Multinational Companies Avoid the Taxman. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2007/nov/06/19

Hussain, H. (2016). What do investigators, government, procurement & tax officers want from a global beneficial ownership register? Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/beneficial-ownership/what-do-investigators-government-procurement-tax-officers-want-from-a-global-beneficial-b6b55190340e

Knobel, A. & A. Cobham (2016). ‘Country-by-country reporting: How restriced access exacerbates global inequalities in taxing rights’, Tax Justice Network report for the Financial Transparency Coalition: http://www.taxjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Access-to-CbCR-Dec16-1.pdf.

KPMG (2016). Country by Country Reporting: An overview and comparison of initiatives. Available at: https://home.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2016/07/cbcr-kpmg-cbcr-overview-and-comparison-of-initiatives-15042016.pdf

Longhorn, M., Rahim, M. & Sadiq, K. (2016). ‘Country-by-country reporting: An assessment of its objective and scope’, eJournal of Tax Research 14(1), pp.4-33. Available at: https://www.business.unsw.edu.au/research-site/publications-site/ejournaloftaxresearch-site/Documents/01_LonghornRahimSadiq_Country_By_Country_Reporting.pdf.

MacKenzie, D. (2008). An Engine, Not a Camera: How Financial Models Shape Markets. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Murphy, R. (2003). A Proposed International Accounting Standard: Reporting Turnover and Tax by Location. Essex: Association for Accountancy and Business Affairs. Available at: http://visar.csustan.edu/aaba/ProposedAccstd.pdf.

Murphy, R. (2012). Country-by-Country Reporting: Accounting for globalisation locally. London: Tax Justice Network. Available at: http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Documents/CBC2012.pdf.

Murphy, R., Christensen, J. & Kimmis, J. (2005). Tax Us if You Can: The True Story of a Global Failure. London: Tax Justice Network. Available at: http://www.taxjustice.net/cms/upload/pdf/tuiyc_-_eng_-_web_file.pdf

PwC (2013). Tax Transparency and Country-by-Country Reporting: An Ever Changing Landscape. Available at: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/tax/publications/assets/pwc_tax_transparency_and-country_by_country_reporting.pdf

Rogers, R. (2013). Digital Methods. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Seabrooke, L., & Wigan, D. (2015). Powering Ideas Through Expertise: Professionals in Global Tax Battles. Journal of European Public Policy, 0(0), 1–18.

Ting, A. (2014). iTax - Apple's International Tax Structure and the Double Non-Taxation Issue. British Tax Review 1. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2411297.